Name the Collective Organization That Protests the Unequal Treatment of Women in the Arts Quizlet

| Formation | 1985 |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | New York City, United States |

| Region served | Worldwide |

| Official linguistic communication | English |

| Website | guerrillagirls |

Guerrilla Girls is an bearding group of feminist, female person artists devoted to fighting sexism and racism within the fine art world.[1] The group formed in New York City in 1985 with the mission of bringing gender and racial inequality into focus within the greater arts community.[2] The group employs culture jamming in the course of posters, books, billboards, and public appearances to expose discrimination and corruption. They also frequently utilise humour in their work to brand their serious messages engaging.[3] They are known for their "guerilla" tactics, hence their name, such as hanging up posters or staging surprise exhibitions.[3] To remain anonymous, members don gorilla masks and employ pseudonyms that refer to deceased female artists such as Frida Kahlo, Kathe Kollwitz, and Alice Neel. Co-ordinate to GG1, identities are curtained considering issues matter more than private identities, "Mainly, we wanted the focus to be on the problems, not on our personalities or our own piece of work."[4]

History [edit]

During the height of the gimmicky art movement in the 20th century, many distinguished galleries lacked appropriate representation of female artists and curators. These galleries were ofttimes privately funded past elites, predominately white males, pregnant that museums are no longer documenting art, but power structures.[5] Past the mid 1960s, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York had a predominantly male board of directors. This correlates to the disparity of female artists on display while art depicting the female person form was abundant. Then in 1985, a group was formed to bring low-cal to these disparities in the sexist fine art world. Membership has fluctuated over the years from a high of about xxx women to a scattering of active members now[vi]

In the spring of 1985, seven women launched the Guerrilla Girls in response to the Museum of Modern Art's exhibition "An International Survey of Recent Painting and Sculpture" [1984), whose roster of 165 artists included only xiii women.[7] Inaugurating MoMA's newly renovated and expanded building, this exhibition claimed to survey that era's virtually of import painters and sculptors from 17 countries.[8] The proportion of artists of color was even smaller, and none of them were women.[9]

Guerrilla Girls at the V&A Museum, London

A comment past the bear witness'southward curator, Kynaston McShine, farther highlights that era'due south explicit fine art globe gender bias: "Kynaston McShine gave interviews saying that whatsoever artist who wasn't in the show should rethink his career."[x] In reaction to the exhibition and McShine's overt bias, they protested in front end of MoMA. Thus, the Guerrilla Girls were born.

When the protests yielded little success, the Guerrilla Girls wheat-pasted posters throughout downtown Manhattan, particularly in the SoHo and East Hamlet neighborhoods.[11]

Soon later on, the group expanded its focus to include racism in the art world, attracting artists of color. They also took on projects outside of New York, enabling them to address sexism and racism nationally and internationally. Though the art world has remained the group's main focus, the Guerrilla Girls' agenda has included sexism and racism in films, mass and popular culture, and politics. Tokenism likewise represents a major grouping concern.[11]

Guerrilla Girls Portfolio Exhibition, Mjellby Art Museum, Sweden. September 29, 2018 – January 27, 2019.

During its get-go years, the Guerrilla Girls conducted "weenie counts," such that members visited institutions like the Metropolitan Museum of Art and counted artworks' male person-to-female subject ratios. Data gathered from the Met'due south public collections in 1989 showed that women artists had produced less than five% of the works in the Mod Art Department, while 85% of the nudes were female.

Early organizing was based effectually meetings, during which members evaluated statistical data gathered regarding gender inequality within the New York Urban center's art scene. The Guerrilla Girls as well worked closely with artists, encouraging them to speak to those within the customs to bridge the gender gap where they perceived it.[12]

Guerrilla Girls wear gorilla masks whenever making public appearances.

When asked about the masks, the girls answer "We were Guerrillas before we were Gorillas. From the beginning, the printing wanted publicity photos. We needed a disguise. No one remembers, for sure, how nosotros got our fur, but one story is that at an early meeting, an original girl, a bad speller, wrote 'Gorilla' instead of 'Guerrilla.' It was an enlightened mistake. Information technology gave us our 'mask-ulinity.'"[13] In an interview with New York Times the Guerrilla Girls were quoted, "Anonymous free spoken language is protected by the Constitution. You'd exist surprised what comes out of your mouth when you wear a mask."[14]

Since 1985, the Guerrilla Girls have worked for an increased awareness of sexism and greater accountability on the part of curators, art dealers, collectors, and critics.[15] The grouping is credited, to a higher place all, with sparking dialogue, and bringing national and international attention to issues of sexism and racism inside the arts.

Influences [edit]

Many feminist artists in the 1970s dared to imagine that female artists could produce authentically and radically unlike art, undoing the prevailing visual epitome. The pioneering feminist critic, Lucy Lippard curated an all-women exhibition in 1974, effectively protesting what virtually deemed a deeply flawed approach, that of just assimilating women into the prevailing art system.[xvi] Shaped past the 1970s women's movement, the Guerrilla Girls resolved to devise new strategies. Most noticeably, they realized that 1970s-era tools such as pickets and marches proved ineffective, as evidenced by how hands MoMA could ignore 200 protestors from the Women'south Conclave for Fine art. "We had to have a new image and a new kind of language to appeal to a younger generation of women," recalls 1 of the founding Guerrilla Girls, who goes by "Liubov Popova."[17] The Guerrilla Girls sought an alternative approach, one that would defeat views of the 1970s Feminist movements as human being-hating, anti-maternal, strident, and humorless:[16] Versed in poststructuralist theories, they adopted 1970s initiatives, merely with a dissimilar language and style. Before feminists tackled grim and unfunny issues such as sexual violence, inspiring the Guerrilla Girls to go along their spirits intact by approaching their piece of work with wit and laughter, thus preventing a backlash.[16]

Work: actions, posters and billboards [edit]

Fine art world [edit]

French feminist group La Barbe (Beard) meets the Guerrilla Girls at the Palais de Tokyo (Paris, 2013).

Throughout their existence, the Guerrilla Girls take gained the nigh attention for their bold protestation art.[18] The Guerrilla Girls' projects (by and large posters at showtime) express observations, concerns, and ideals regarding numerous social topics. Their fine art has always been fact-driven, and informed by the group's unique approach to information collection, such equally "weenie counts." To be more inclusive and to make their posters more eye-communicable, the Guerrilla Girls tend to pair facts with humorous images[19] – a form of word fine art.[xx] Although the Guerrilla Girls gained fame for wheat-pasting provocative entrada posters around New York Metropolis, the group has too enjoyed public commissions and indoor exhibitions.

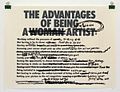

In addition to posting posters around downtown Manhattan, they passed out thousands of pocket-sized handbills based on their designs at various events.[12] The first posters were mainly black and white fact sheets, highlighting inequalities between male and female person artists with regard to a number of exhibitions, gallery representation, and pay. Their posters revealed how sexist the art earth was in comparison to other industries and to national averages. For case, in 1985 they printed a poster showing that the salary gap in the art world between men and women was starker than the United states boilerplate, proclaiming "Women in America earn only 2/3 of what men practise. Women artists earn only i/iii of what men exercise." These early posters often targeted specific galleries and artists. Some other 1985 poster listed the names of some of the nigh famous working artists, such every bit Bruce Nauman and Richard Serra. The poster asked "What practice these artists take in mutual?" with the respond "They let their work to be shown in galleries that bear witness no more than 10% of women or none at all."

The group was besides activists for equal representation of women in institutional fine art, and highlighted artist Louise Bourgeois in their "Advantages to Being a Women artist," affiche in 1988 as one line read, "Knowing your career might not pick up till after you lot're fourscore."[21] Their pieces are also notable for their use of combative statements such as "When racism and sexism are no longer fashionable, what volition your art collection exist worth?"[11]

"Beloved Fine art Collector" (1986) is a 560x430 mm screen-print on paper. This is ane of thirty posters published in a portfolio entitled "Guerrilla Girls Talk Back".[22] This impress is unusual in the portfolio in that information technology takes the course of an enlarged handwritten letter on infant pink paper. The extremely rounded cursive script crowned with a frowning flower exudes femininity, symbolizing the biting sarcasm for which the Guerrilla Girls were known. The Guerrilla Girls sent this poster to well-known art collectors across the United States, pointing out how few works they endemic by women artists. This send-up of femininity is aimed at the expectation that, even when presenting a serious complaint, women should do then in a socially acceptable 'nice' mode. "We know that you feel terrible nearly this" appeals to the feelings of the recipient. This piece was a commentary on how difficult it is for female person artists, and what lengths they must go through in lodge to be recognized and taken seriously. Women are constantly expected to perform a sure way and this impress is the embodiment of how tumultuous it is for women all around the world to be recognized in the eyes of men with power. The group after transcribed information technology into other languages and sent information technology to collectors outside the U.S. A applied joke with serious implications, this affiche is now (somewhat ironically) a collector's item.

The posters were rude; they named names and they printed statistics (and almost always cited the source of those statistics at the bottom, making them difficult to dismiss). They embarrassed people. In other words, they worked.[23]

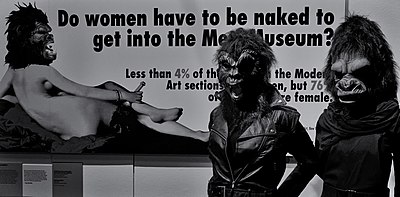

The Guerrilla Girls' offset colour poster, which remains the group's most iconic image, is the 1989 Metropolitan Museum affiche, which used information from the group's first "weenie count." In response to the overwhelming number of female person nudes counted in the Modern Art sections, the poster asks, sarcastically, "Practice women have to be naked to get into the Met. Museum?". Side by side to the text is an prototype of the Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres painting La Grande Odalisque, one of the nearly famous female person nudes in Western art history, with a gorilla head placed over the original face.

In 1990, the group designed a billboard featuring the Mona Lisa that was placed along the Westward Side Highway supported by the New York City Public Art Fund.[24] For ane day, New York'southward MTA Bus Visitor likewise displayed coach advertisements with Met. Museum affiche. Stickers also became a pop calling cards representative of the grouping.

The Guerrilla Girls infiltrated the bathrooms of the newly opened Guggenheim Soho, placing stickers regarding female inequality on the walls.[12] In 1998, Guerrilla Girls West protested at the San Jose Museum of Art, over low representation of women artists.[25]

In addition to researching and exposing sexism in the art globe, the Guerrilla Girls accept received commissions from numerous organizations and institutions, such equally The Nation (2001),[26] Fundación Bilbao Arte (2002), Istanbul Modernistic (2006) and Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art (2007). They have also partnered with Immunity International, contributing pieces to a show nether the arrangement'south "Protect the Man" initiative.[27]

They were interviewed for the film !Women Fine art Revolution.[28]

In 1987, the Guerrilla Girls[29] published thirty posters in a portfolio entitled Guerrilla Girls Talk Back.[30] Ane specifically, We Sell White Bread,[31] was a poster made to gradually widen their focus, tackling issues of racial discrimination in the art world and likewise making more direct, politicized interventions.[32] [31] In 1987, the image on this poster was first seen every bit peel-off stickers on gallery windows and doors in New York.[33] Its medium, screen print on paper, has the words "We Sell White Breadstuff" and are stamped on a slice of white bread alongside a listing of ingredients that includes the white male person artists whose work is on display at the galleries.[32] [31] According to the poster, the galleries favored white, male artists, noting that the gallery "contains less than the minimum daily requirement of white women and non-whites."[32] [33]

Public commissions [edit]

In 2005, the group exhibited large-format posters Welcome to the Feminist Biennale at the Venice Biennale (the first in 110 years to be overseen by women), scrutinizing 101 years of Biennale history in terms of variety. Where Are the Women Artists of Venice? explored the fact that most works owned by Venice'due south historical museums are kept in storage.[34] [35] [36]

Since 2005, the Guerrilla Girls accept been invited to produce special projects for international institutions, sometimes for the very institutions, they accept criticized. Offers that pose a dilemma are carefully considered, so as to avoid censure since one way to better institutions is to criticize them from within.[37]

Their 2006 affiche The Future For Turkish Women Artists as Revealed by the Guerrilla Girls, deputed past Istanbul Modern, demonstrated that the condition of women artists in Turkey was meliorate than in Europe.[38] In 2007, the Washington Post published their Horror on the National Mall!, a one-folio newspaper spread attacking the absence of diversity amongst revenue enhancement-payer supported museums on the Mall in Washington, DC.[39] During the 2007 Art-ATHINA, the Guerrilla Girls projected "Honey Art Collector" in Greek onto the entrance's façade. In 2015, they projected their "Dear Art Collector" animation onto a museum façade, taking on collectors who fail to pay employees a living wage.[twoscore] To commemorate the 20th Anniversary of the École Polytechnique massacre, the University of Quebec commissioned their Troubler Le Repos (Disturbing The Peace) poster, whose texts addressed anti-women hate-speech since Aboriginal Greece to Rush Limbaugh.

In 2009, they launched I'1000 not a feminist, but If I were this is what I'd complain about ... , an interactive graffiti wall that enables women who don't see themselves equally feminists the means to target gender issues with the promise that active participation will broaden their perspectives.[41] In 2012, this traveled to Krakòw's Art Boom Festival.[42]

In 2011, Columbia College Chicago's Drinking glass Mantle Gallery and Found for Women and Gender in the Arts and Media deputed the first Guerrilla Girls survey of Chicago museums. The resulting banner entitled Chicago Museums [Guerrilla Girls to Museums: Time for Gender Reassignment!] critiqued gender disparity in the contemporary art collections of the Art Institute of Chicago and the Museum of Contemporary Art.[43]

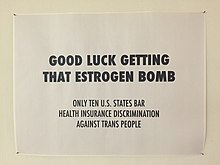

In 2012, an advertising truck towed Do women Have To Be Naked To Get into Boston Museums? around Boston.[44] Invited by Yoko Ono to participate in the 2013 Meltdown Festival, the Guerrilla Girls updated their 2003 Estrogen Bomb poster, which had premiered in The Village Voice in 2003.

During Winter 2016, they participated in "Twin Urban center Takeover," art exhibitions and art projects organized by a consortium of local art organizations sited around Minneapolis and St. Paul.[45] [46] [47] [48] [49]

In 1996 Guerrilla Girls came out with Planet Pussy in Monkey Concern issue #4 in November 1996.[50] This was a work nearly feminism and was published past Sike Burmeister and Sabine Schmidt.[51]

Movie world [edit]

Guerrilla Girls billboard in Los Angeles protesting white male person dominance at the Oscars in 2002.

To protest the dearth of female directors, the Guerrilla Girls distributed stickers during the 2001 Sundance Moving-picture show Festival.[52] The Nation invited them to present Birth of Feminism,[26] which they updated and presented in 2007 as a banner outside Witte de With Center for Contemporary Arts. Since 2002, Guerrilla Girls Inc. accept designed and installed billboards during the Oscars that address white male dominance in the film industry, such equally: "Anatomically Correct Oscars," "Even the Senate is More Progressive than Hollywood," "The Birth of Feminism,"[53] "Unchain the Women Directors."[54]

During the 2015 Reykjavik Arts Festival, the Guerrilla Girls displayed National Film Quiz, a billboard criticizing the fact that 87% of national funding for films goes to men, despite women playing an important function of Iceland'south public and private sectors.[55] In lite of 2016's #Oscarssowhite entrada, the Guerrilla Girls updated the above billboards, presenting them on downtown Minneapolis streets for "Twin City Takeover."[56]

Politics and social issues [edit]

Although the Guerrilla Girls' protest art directed at the fine art world remains their virtually well-known piece of work, throughout their existence the group has periodically targeted politicians, specifically conservative Republicans. Those criticized have included George Bush, Newt Gingrich, and nigh recently Michele Bachmann. In 1991, the Creative person and Homeless Collaborative invited them to piece of work with homeless women to create posters in response to homelessness and the beginning Gulf War. Between 1992 and 1994, Guerrilla Girl posters addressed the 1992 Presidential election, reproductive rights (done for the march on Washington in 1992), gay and lesbian rights, and the LA riots. During the 2012 election, they displayed their Even Michele Bachman believes. ... on a billboard adjacent to a football game stadium to advertise her plan to: ban same-sex marriages, require Voter Id Checks, and spend money implementing statewide voter IDs.[57] Their 2013 posters discussed the Homeland Terror Alarm system and Arnold Schwarzenegger'southward gubernatorial entrada.

In 2016, the Guerrilla Girls launched the "President Trump Announces New Commemorative Months" campaign in the form of stickers and posters, which they distributed during the "Women's March on Washington" in LA and NYC, as well every bit the J20 event at the Whitney Museum of Art[58] and the Fire Fink protestation at MoMA.[59]

Work: publications and merchandise [edit]

To shed calorie-free on inequality in the art world, the Guerrilla Girls take published numerous books. In 1995, they published their commencement volume, Confessions of the Guerrilla Girls, a compilation of l works plus a self-interview.[sixty] [61] In 1998, they published The Guerrilla Girls Bedside Companion to the History of Western Art, a consciousness-raising comic book that sold 82,000 copies, as it explores how art history's male domination constrained several female artists' careers.[62] In 2003, they published Bitches, Bimbos and Ballbreakers, a down and dirty catalogue of "The Top Stereotypes from Cradle to Grave." Offering thumbnail histories for cultural clichés ranging from "Daddy's Girl," "the Girl Next Door," "the Bimbo/Dumb Blonde" to "the Bowwow /Ballbreaker", each is given "trademark Guerrilla Girl treatment: pointed factoids and cool graphics."[63] [64]

Their 2004 book The Guerrilla Girl's Museum Activity Book (reissued in 2012) parodies children's museum activity books. Meant to teach children how to both appreciate and critique museums, this book provides activities that reveal the problematic aspects of museum culture and major museum collections. In 2009, they produced a history of hysteria, The Hysterical Herstory Of Hysteria And How Information technology Was Cured From Ancient Times Until At present.[65] MFC-Michèle Didier published it in 2016.

Presentations [edit]

An of import part of Guerrilla Girls' outreach since 1985 has been presentations and workshops at colleges, universities, fine art organizations, and sometimes at museums. The presentations, known every bit "gigs", concenter hundreds and sometimes thousands of attendees. In the gig, they play music, videos, bear witness slides and talk about the history of their piece of work, how information technology has evolved. In the end, the GGs interact with audition members. New work is always included and gig fabric changes all the time. They have done hundreds of these events and accept traveled to nearly every state also equally Europe, South America, and Australia.

In recognition of their piece of work, the Guerrilla Girls accept been invited to give talks at earth-renowned museums, including a presentation at the MoMA's 2007 "Feminist Futures" Symposium. They have too been invited to speak at art schools and universities across the globe and gave a 2010 commencement speech at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. To mark the 30th anniversary of the Guerrilla Girls, Matadero Madrid hosted "Guerrilla Girls: 1985-2015," an exhibition featuring most of the collective's product accompanied by a series of events including a talk/performance past Guerrilla Girl members Frida Kahlo and Käthe Kollwitz.[66] [67] The exhibition also showed the 1992 documentary "Guerrilla in Our Midst" by Amy Harrison.[68] [69]

Iii Guerrilla Girls appeared on the Stephen Colbert show on January 14, 2016.[70] [71]

Exhibitions [edit]

Early solo exhibitions included: "The Night the Palladium Apologized" (1985), Palladium (New York City); "Guerrilla Girls Review the Whitney" (1987), Clocktower PS1; and "Guerrilla Girls" (1995), Printed Affair, Inc[72]

Career surveys include:

- "Guerrilla Girls Talk Back: The Get-go 5 Years, A Retrospective: 1985-1990" (1991), the Falkirk Cultural Center, San Rafael, California

- "Guerrilla Girls: 1985-2013," Azkuna Zentroa (2013).

- "Guerrilla Girls: Retrospective" (2009), Millennium Court Arts Centre, Uk *"Feminist Masked Avengers: xxx Early Guerrilla Girls' Posters" (2011) Mason Gross Schoolhouse of the Arts Galleries

- "Guerrilla Girls" (2007), Hellenic American Union Galleries, Athens, GR

- "Not Fix to Make Nice: The Guerrilla Girls in the Art World and Beyond" Columbia College Chicago (2012-2017) Traveled to Monserrat Higher of Art; Krannert Art Museum; Fairfield University; Georgia Museum of Art; DePauw Academy; North Michigan University: Stony Brook University: California State University: The Verge Centre for the Arts: and Moore College for Art and Design.

- "The Guerrilla Girls" (2002), Fundacíon Bilbao Arte, Bilbao, ES

- "Guerrilla Girls: Takeover" (2021), Nasher Sculpture Centre, Dallas, Texas.

On the heels of "Not Prepare to Make Squeamish" were:

- "Art at the Center: Guerrilla Girls'," 2016, Walker Art Eye[73]

- "Front Room: Guerrilla Girls," 2016–2017, Baltimore Museum of Art

- "Guerrilla Girls: Not Prepare to Brand Nice, 30 Years and Still Counting," 2015, Abrons Arts Eye;[6]

- "Media Networks: Andy Warhol and the Guerrilla Girls," 2016, Tate Modern[74]

- "Non Fix to Brand Nice: Guerrilla Girls 1985-2016," 2016–2017, FRAC Lorraine.

- "The Guerrilla Girls and La Barbe", 2016, Gallery mfc-micheledidier, Paris.

Controversies [edit]

Diversity [edit]

Despite having routinely challenged fine art institutions to display more artists of colour, both members and critics want the Guerrilla Girls to be more diverse. "Zora Neale Hurston" recalls Guerrilla Girl membership as "more often than not white" and largely mirroring the art earth demographics that they critiqued.[75] Despite sporting gorilla masks to downplay personal identity, some members attribute Guerrilla Girl interests to the fact that de facto leaders "Frida Kahlo" and "Kathe Kollwitz" are both white.[16] ("Frida Kahlo" has too been criticized for her appropriation of a Latina creative person'south name.)[76] The artist believed in the overt artistic expression by correlating dazzler and pain, forth with the ascent of modernism.[77] An fine art movement without generalization.

Nonetheless, any precise information on the demographics of the Guerrilla Girls is impossible, for they have "staunchly, and problematically, resisted being surveyed as to the makeup of their own membership."[16]

Several Guerrilla Girls who are people of color have faced numerous challenges. Despite the Guerrilla Girls' stance confronting tokenism, some artists of color abased Guerrilla Girl membership due to tokenism, silencing, boldness, and whitewashing.[sixteen] [75] As a woman of color, "Alma Thomas" describes having felt uncomfortable wearing the Guerrilla Girls' signature gorilla mask.[78] "Thomas" recalls picayune endeavour being devoted to understanding the challenges of artists of color. "Their whiteness was such that they. ... didn't understand that blacks were being put in a completely dissever earth in the art earth, that black male artists and black female person artists are completely separated, completely segregated to this twenty-four hour period."[75] Ultimately, this widespread antagonism led to many "artists of colour [leaving] afterwards a few meetings because they could sense the unspoken bureaucracy in the group."[79]

Second-wave feminism and essentialism [edit]

Anonymous MCAD student protest against the Guerrilla Girls

Emerging at the tail cease of the 2nd-wave feminist movement, the Guerrilla Girls navigated the differences between established and emerging feminist theory during the 1980s. "Alma Thomas" describes this grey-surface area that the Guerrilla Girls occupied equally "universalist feminism," bordering on essentialism.[78] Art Historian Anna Chave considers the Guerrilla Girls' essentialism much more profound, leading the group to be "assailed past ... a rising generation of women wise in the means of poststructuralist theory, for [their] putative naiveté and susceptibility to essentialism."[sixteen] Essentialist views are nigh clearly exhibited in two Guerrilla Girl books:The Guerrilla Girls Bedside Companion to the History of Western Art (1998) and the controversial Estrogen Bomb (2003–13) campaign. Regarding the former, "Alma Thomas" worried that The Guerrilla Girls Bedside Companion to the History of Western Art "was so embedded in that second-wave feminist and even pre-2d-wave essentialism" that it fulfilled some supposition that all women artists are feminist artists.[78]

Students at Minneapolis Higher of Art and Design criticized their Estrogen Bomb poster entrada, describing it equally insensitive towards transgender people since it ties the female gender to estrogen, the same sort of essentialist link the Guerrilla Girls aim to critique.[80] [81] Aside from essentialism, the Guerrilla Girls have also been critiqued for failing to integrate intersectionality into their piece of work.[76]

Internal disputes [edit]

Leading up to a highly publicized 2003 lawsuit, there was increasing animosity toward "Frida Kahlo" and "Käthe Kollwitz." Despite founding members' initial intention to create a non-hierarchal, equitable power construction, in that location was an increasing sense that two people were making "the final decisions no matter what you said."[75] Several Guerrilla Girls felt that their second book, The Guerrilla Girls Bedside Companion to the History of Western Art,[82] primarily represented the views of "Kahlo" and "Kollwitz". Some fifty-fifty felt that "Kahlo" and "Kollwitz" completely controlled the volume, despite their having selected material created collectively past all Guerrilla Girls. There was even suspicion that these ii non merely claimed all the credit but took all of the profits. Some members condemned the book as "undemocratic and ... against the spirit of the [Guerrilla] Girls."[78]

Every bit the Guerilla Girls gained in popularity, tensions led to what the Girls later chosen the "banana divide," as five members actually split from the collective. Soon after several members stepped aside to form Guerrilla Girls Broadband, "Kahlo" and "Kollwitz" moved to trademark the proper noun "Guerrilla Girls, Inc." to distinguish their realm from those of Guerrilla Girls BroadBand and Guerrilla Girls On Tour! whose focus is discrimination in the theater earth.[79] Even though their former colleague "Gertrude Stein" was in the on-tour group, "Kahlo" and "Kollwitz" charged them with copyright and trademark infringement and unjust enrichment. Many members of the group felt specially betrayed that "Kahlo" and "Kollwitz" had launched their lawsuit under their existent names, Jerilea Zempel and Erika Rothenberg.[83]

This prompted negative reactions from both current and former Guerrilla Girls, who objected to "Kahlo" and "Kollwitz" claiming responsibility for having created the collective endeavor, as well as the flippancy with which they exchanged their anonymity for legal standing.[16]

Gauge Louis L. Stanton, who handled the instance, rejected the "bizarre" suggestion that defendants sporting gorilla masks exist allowed to testify in his courtroom. He also stated that "Mundane courtroom procedures for adjudicating legal rights and the ownership of property require directly and cross-examination of real persons with real addresses and attributes."[83]

In their 45-page complaint, "Kahlo" and "Kollwitz" described themselves every bit the grouping's "guiding forces," fifty-fifty though the Guerrilla Girls were "informally organized, [and] had no official hierarchy." Initially, they asked the court to cease Guerrilla Girls Broadband from calling themselves Guerrilla Girls and sought millions of dollars in amercement. In 2006, they settled with the theatre group who agreed to go by Guerrilla Girls on Tour. Equally of 2013, 3 separate groups remained active, the GuerrillaGirlsBroadBand, Inc., Guerrilla Girls On Tour, Inc. (the Theatre Girls), and Guerrilla Girls, Inc. The Guerrilla Girls BroadBand focuses on the internet as its "natural habitat."[84]

Guerrilla Girls display at Mills College - Public Works: Artists' Interventions 1970s - Now

Selling out [edit]

Upon their 1985 debut, the Guerrilla Girls were "lauded by the very institution they sought to undermine." They have since exhibited at Tate Modern, Venice Biennale, Centre Pompidou, and MoMA, which additionally grants them a broader audition for their concerns.[85] Since then, this relationship has only intensified, every bit the Guerrilla Girls presented their exhibitions in museums and even allowed their works to be collected past hegemonic institutions. Although some take questioned the efficacy, if not hypocrisy, of the group's working inside the system that they originally denigrated, few would claiming their determination to let the Getty Found firm their archives.[76] [85]

Members and names [edit]

2 members of the Guerrilla Girls join a panel discussion at the Rochester Art Center in 2016 in Rochester, Minnesota

Membership in the New York City group is sectional, by invitation only, based on relationships with electric current and past members, and one'due south involvement in the contemporary art world. A mentoring plan was formed within the group, pairing a new member with an experienced Guerrilla Girl to bring them into the fold. Due to the lack of formality, the grouping is comfortable with individuals outside of their base challenge to exist Guerrilla Girls; Guerrilla Girl 1 stated in a 2007 interview: "Information technology tin can only enhance us by having people of power who accept been given credit for beingness a Daughter, fifty-fifty if they were never a Daughter." Men are non allowed to become Guerrilla Girls but may support the group by assisting in promotional activities.[12]

Guerrilla Girls' names are pseudonyms more often than not based on expressionless female artists. Members become by names such as Käthe Kollwitz, Alma Thomas, Rosalba Carriera, Frida Kahlo, Alice Neel, Julia de Burgos, and Hannah Höch. Guerrilla Girls' "Carriera" is credited with the thought of using pseudonyms equally a fashion to not forget female person artists. Having read nigh Rosalba Carriera in a footnote of Messages on Cézanne by Rainer Maria Rilke, she decided to pay tribute to the footling-known female artist with her name. This also helped to solve the trouble of media interviews; the group was oft interviewed by phone and would not give names, causing problems and defoliation among the group and the media. Guerrilla Girl 1 joined in the late 1980s, taking on her proper noun equally a way to memorialize women in the art community who take fallen under the radar and did not brand every bit notable every bit an impact as the names takes on by other members.[12] For some members like "Zora Neale Hurston", or Emma Amos, identities have only been made public posthumously.

Gorilla symbolism [edit]

The 1933 motion picture Male monarch Kong was influential to the concept of a Guerilla Girl.

Female Creative person. Frida Kahlo

The thought to adopt the gorilla equally the grouping's symbol stemmed from a spelling mistake. One of the offset Guerrilla Girls accidentally spelled the group'due south proper noun at a meeting as "gorilla."[fifteen] Despite the fact that the idea of using a gorilla every bit a group symbol might take been accidental, the choice is withal pertinent to the group's overall message in several key ways.

To begin with, the gorilla in popular culture and media is often associated with King Kong, or other images of trapped and tamed apes. In the 2010 SAIC Commencement, the comparison between institutionalized artists and tamed apes was explicitly made:

And concluding, simply not least, exist a bully ape. In 1917, Franz Kafka wrote a short story titled A Written report to An University, in which an ape spoke about what it was like to exist taken into captivity by a agglomeration of educated, intellectual types. The published story ends with the ape tamed and broken by the stultified academics. But in an earlier draft, Kafka tells a different story. The ape ends his report by instructing other apes NOT to let themselves to be tamed. He says instead: pause the confined of your cages, bite a pigsty through them, squeeze through an opening ... and enquire yourself where do Y'all want to go[86]

The gorilla is also typically associated with masculinity. The Met Museum affiche is in part shocking because of its juxtaposition of the eroticized female odalisque body, and the large, snarling gorilla head. The add-on of the head detracts from the male gaze and changes the mode in which viewers are able to look at or sympathise the highly sexualized prototype. Further, the add-on of the gorilla questions and modifies stereotypical notions of female beauty within Western fine art and popular culture, some other stated goal of the Guerrilla Girls.

The original image by Ingres without the addition of the gorilla head represents the kind of art that the Guerrilla Girls take issues with, like the common bug of exoticism and sexualization of women.

Guerrilla Girls, who habiliment the masks of big, hairy, powerful jungle creatures whose beauty is hardly conventional ... believe all animals, large and small, are beautiful in their own manner.[87]

Though this goal has never been explicitly stated by the group, in the history of Western art, primates have often been associated with the visual arts, and with the figure of the creative person. The idea of ars simia naturae ("fine art the ape of nature") maintains that the job of art is to "ape", or faithfully copy and represent nature. This was an idea first popularized by Renaissance thinker Giovanni Boccaccio who alleged that "the artist in imitating nature only follows Nature'southward own command."[88]

Notable collections [edit]

- Art Found of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois[89]

- Heart for the Study of Political Graphics, Culver Urban center, California[ninety] [91]

- Fales Library and Special Collections, New York University, New York City[92]

- Madison Museum of Contemporary Fine art, Madison, WI

- Museum of Modern Art, New York City[11]

- Tate, United Kingdom[93]

- Walker Art Centre, Minneapolis, Minnesota[94]

- Whitney Museum of American Art, New York City[95]

Notable exhibitions [edit]

- Art at the Middle: Guerrilla Girls, 2016, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, Minnesota[73]

- Beyond the Streets, 2018, Los Angeles[96]

- Guerrilla Girls Printed Affair, 1995, 77 Wooster Street, SoHo[72]

- Guerrilla Girls Review the Whitney, 1987, The Clocktower, New York City[12]

- Guerrilla Girls: Exposición Retrospectiva, 2013, Alhóndiga Bilbao, Bilbao, Kingdom of spain[69]

- Guerrilla Girls: Not Ready to Brand Nice, 30 Years and Still Counting, Abron Arts Center, New York City[6]

- Media Networks: Andy Warhol and the Guerrilla Girls, (display), 2016, Tate Modern, London, United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland[74]

- Not Ready to Make Prissy: Guerrilla Girls in the Artworld and Beyond, 2012–2017, Columbia Higher Chicago, Chicago Illinois (traveled to ten boosted venues around the US)

- The Nighttime the Palladium Apologized, 1985, Palladium, New York City

Legacy [edit]

-

Ridykeulous, The Advantages of Existence a Adult female Lesbian Creative person, 2007.

Come across also [edit]

- Feminist art criticism

- Feminist art movement in the U.s.

- Guerrilla Girls On Tour

References [edit]

- "Artist, Curator & Critic Interviews". !Women Art Revolution - Spotlight at Stanford. 2018. Archived from the original on August 23, 2018. Retrieved August 23, 2018.

Notes [edit]

- ^ "Guerrilla Girls". Tate.

- ^ Brockes, Emma (Apr 29, 2015). "The Guerrilla Girls: xxx years of punking art earth sexism". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved April three, 2020.

- ^ a b "Guerrilla Girls | Artist Profile".

- ^ "Guerilla Girls Bare All". Archived from the original on Jan 13, 2014.

- ^ "The Guerrilla Girls' fight against bigotry in the art world | DW | March viii, 2017". DW.COM . Retrieved Apr 3, 2020.

- ^ a b c Ryzik, Melena (Baronial five, 2015). "The Guerrilla Girls, Afterwards iii Decades, All the same Rattling Art World Cages". The New York Times.

- ^ "MoMA Fact Sheet" (PDF).

- ^ Brenson, Michael (April 21, 1984). "A Living Artists Show at the Modern Museum". The New York Times . Retrieved February 27, 2013.

- ^ "African American Artists Are More Visible Than Ever. So Why Are Museums Giving Them Short Shrift?". artnet News. September 20, 2018. Retrieved April three, 2020.

- ^ Confessions of the Guerrilla Girls, with an essay by Whitney Chadwick. New York: Harper Perennial. 1995. p. 13. ISBN9780060950880.

- ^ a b c d Cooper, Ashton (2010). "Guerrilla Girls speak on social injustice, radical art". A&East. Columbia Spectator. Retrieved April 20, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f Richards, Judith Olch (2007). "Interview with Guerrilla Girls Rosalba Carriera and Guerrilla Girl 1". Archives of American Art. Retrieved June 10, 2011.

- ^ "Interview". Guerrilla Girls. Archived from the original on January 13, 2014. Retrieved July thirty, 2014.

- ^ "Interview Mag". Guerrilla Girls. Archived from the original on August 5, 2014. Retrieved July 30, 2014.

- ^ a b "Guerrilla Girls Blank All: An Interview". Guerrilla Girls. Archived from the original on January 13, 2014. Retrieved January xviii, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Chave, Anna C. "The Guerrilla Girls' Reckoning." Art Journal lxx.ii (2011): 102-xi. Web.

- ^ "Oral history interview with Guerrilla Girls Elizabeth Vigée LeBrun and Liubov Popova." January nineteen, 2008. Athenaeum of American Fine art. Smithsonian Establishment.

- ^ "Brooklyn Museum: Guerrilla Girls". world wide web.brooklynmuseum.org . Retrieved April 19, 2019.

- ^ Carpetbagger. "Women in Bondage." New York Times, January 24, 2006. https://carpetbagger.blogs.nytimes.com/2006/01/24/women-in-chains/

- ^ Cohen, Alina (January v, 2019). "13 Artists Who Highlight the Ability of Words". Artsy . Retrieved May 19, 2021.

- ^ Louise Conservative; The Spider, The Mistress & The Tangerine. Directed by Marian Cajori and Amei Wallach. 2008. New York, NY: Zeitgeist Films, 2009. DVD

- ^ "Guerilla Girls Talk Dorsum". Tate Modern . Retrieved March 2, 2020.

- ^ Tallman, Susan (1991). "Guerrilla Girls" (PDF). Arts Magazine. 65 (8): 21–2. Archived from the original (PDF) on July two, 2013. Retrieved February 27, 2013.

- ^ Rhyner, Stephanie (May 1, 2015). "Satirical Warfare: Guerrilla Girls' Performance and Activism from 1985-1995". University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, Theses and Dissertations.

- ^ "Masking for Art". Metro. April 29, 1998.

- ^ a b "April ii, 2001 Result". April 2, 2001.

- ^ "Press releases in 2014". Amnesty International UK. Archived from the original on Feb 13, 2012. Retrieved January xviii, 2014.

- ^ Anon 2018 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFAnon2018 (help)

- ^ "Guerrilla Girls", Wikipedia, March thirty, 2021, retrieved April 9, 2021

- ^ "The Guerrilla Girls Talk Back: Exhibited past the National Museum of Women in the Arts". NMWA . Retrieved April ix, 2021.

- ^ a b c "CMOA Drove". collection.cmoa.org . Retrieved April 9, 2021.

- ^ a b c "We sell white bread (2012-143.17)". artmuseum.princeton.edu . Retrieved April ix, 2021.

- ^ a b "'We Sell White Breadstuff', Guerrilla Girls, 1987". Tate . Retrieved April 9, 2021.

- ^ Robinson, Walter. "Festive Venice". Artnet . Retrieved Feb 27, 2013.

- ^ "Girl power". The Economist. June ii, 2005.

- ^ Carol Vogel. "Subdued Biennale forgoes stupor factor." The New York Times. June 13, 2005

- ^ "Guerrilla Girl Gig," SUNY Stony Brook, NY, October 2016

- ^ http://vis129f.wikifoundry.com/page/Guerrilla+Girls%3A+"The+Future+for+Turkish+Women+Artists"-+Nicole+Young [ permanent dead link ]

- ^ "Museums & Galleries: Feminism & Art - Guerrilla Girls Raid A Male Stronghold (washingtonpost.com)". The Washington Post.

- ^ Falkenstein, Michelle (November 1, 2000). "Framing".

- ^ "Guerrilla Girls Take On Irish Arts Exclusion of Women " Latest News " The National Women'due south Council of Ireland". www.nwci.ie.

- ^ "Guerrilla Girls Plant a Flop". HuffPost UK. June 19, 2013.

- ^ Page-Lieberman, Neysa, ed. (2012). Non Prepare to Make Overnice: Guerrilla Girls in the Artworld and Across. Chicago, Illinois. ISBN978-0929911434. OCLC 785746022.

- ^ "Guerrilla Girls launch art protest targeting MFA - The Boston Globe". BostonGlobe.com.

- ^ "Archived re-create". Archived from the original on February 23, 2017. Retrieved February 22, 2017.

{{cite spider web}}: CS1 maint: archived re-create as title (link) - ^ "11 Posters Celebrating 30 Years of the Guerrilla Girls". walkerart.org.

- ^ "Guerrilla Girls: giving the art earth hell since 85'". Dazed. Feb one, 2016.

- ^ [1] [ dead link ]

- ^ "The Guerrilla Girls Take Minnesota". Vogue. Jan 21, 2016.

- ^ "CHRONOLOGY: BIBLIOGRAPHY". Guerrilla Girls.

- ^ "Planet pussy". Planet Pussy. Nov 1, 2021. OCLC 501337396 – via Open WorldCat.

- ^ Rich, B. Ruby (February 8, 2001). "The West Indies" – via world wide web.thenation.com.

- ^ http://www.juliethebolt.cyberspace/page/folio/319287.htm Archived March 25, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Guerrilla Girls vs. King Kong". Fine art-for-a-change.com. February 5, 2006. Retrieved Jan 18, 2014.

- ^ "From Iceland – The Boys' Gild: Men Are Strong And Comport Around Big Cameras?". The Reykjavik Grapevine. June 24, 2015.

- ^ "EXHIBITIONS". Guerrilla Girls.

- ^ "Archives". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Russeth, Andy Battaglia; Battaglia, Andy; Russeth, Andrew (January 20, 2017). "'Speak Out on Inauguration Twenty-four hour period': Words at the Whitney Museum Take Aim at Trump".

- ^ Vartanian, Hrag (Feb 23, 2017). "Protesters Demand MoMA Driblet Trump Advisor from Its Board". Hyperallergic.

- ^ Confessions of the Guerrilla Girls. 1995. ISBN0060950889.

- ^ Mark Dery. "Art Attack." The New York Times Book Review. July 30, 1995

- ^ Girls, Guerrilla (1998). The Guerrilla Girls' Bedside Companion to the History of Western Art. ISBN014025997X.

- ^ Hoban, Phoebe (January iv, 2004). "Masks Still in Place just Firmly in the Mainstream", The New York Times.

- ^ Zeisler, Andi. "Bitches, Bimbos and Ballbreakers".

- ^ "Books by the Guerrilla Girls". Guerrilla Girls. Retrieved December 29, 2016.

- ^ "Guerrilla Girls 1985-2015". MataderoMadrid . Retrieved March 5, 2016.

- ^ "GUERRILLA GIRLS CONFERENCIA / Functioning". Vimeo. February 9, 2015. Retrieved March v, 2016.

- ^ "Guerrillas in Our Midst". Women Brand Movies . Retrieved March 5, 2016.

- ^ a b "GUERRILLA GIRLS. Exposición retrospectiva | Bilbao International". www.bilbaointernational.com. Archived from the original on September 21, 2016. Retrieved May 24, 2016.

- ^ "Guerrilla Girls Talk The History Of Art vs. The History Of Ability". youtube.com. The Late Testify with Stephen Colbert. January xiv, 2016. Archived from the original on December 12, 2021.

- ^ Miller, One thousand.H. (January 14, 2016). "Here Are the Guerrilla Girls on 'The Late Bear witness with Stephen Colbert'". Artnews . Retrieved May twenty, 2017.

- ^ a b Cotter, The netherlands (Feb 10, 1995). "Fine art in Review". The New York Times.

- ^ a b "Art at the Middle: Guerrilla Girls — Calendar — Walker Fine art Center". www.walkerart.org . Retrieved May 24, 2016.

- ^ a b "Andy Warhol and the Guerrilla Girls | Tate". www.tate.org.great britain. Archived from the original on May fifteen, 2016. Retrieved May 24, 2016.

- ^ a b c d Richards, Judith Olch; Hurston, Zora Neale; Martin, Agnes (May 17, 2008). "Oral history interview with Guerrilla Girls Zora Neale Hurston and Agnes Martin, 2008 May 17 - Oral Histories | Athenaeum of American Fine art, Smithsonian Institution". world wide web.aaa.si.edu . Retrieved June seven, 2016.

- ^ a b c Lodu, Mary (March 2016). "No No'due south: Guerrilla Girls at the State Theatre". INREVIEW.

- ^ "Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera and the ascension of Mexican Modernism". Huck Magazine. Oct 24, 2019. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Richards, Judith Olch; Bowles, Jane; Thomas, Alma (May 8, 2008). "Oral history interview with Guerrilla Girls Jane Bowles and Alma Thomas, 2008 May 8 - Oral Histories | Athenaeum of American Fine art, Smithsonian Institution". www.aaa.si.edu . Retrieved June 7, 2016.

- ^ a b Stein, Gertrude (Summer 2011). "Guerrilla Girls and Guerrilla Girls BroadBand: Inside Story". Fine art Journal. 70 (2): 88–101. doi:ten.1080/00043249.2011.10791003. JSTOR 41430727. S2CID 143639127.

- ^ Cherneff, Lila, 2015-12-28, "Guerrilla Girls Stumble at MCAD," Radio Plan, https://soundcloud.com/minneculture/guerrilla-girls-stumble-at-mcad, 2016-05-31, KFAI

- ^ Jones, Hannah (April 20, 2016). "The Guerrilla Girls, 'estrogen bombs' and exclusionary feminism". Twin Cities Daily Planet. Adaobi Okolue. Retrieved June 7, 2016.

- ^ "The Guerrilla Girls' Bedside Companion to the History of Western Art (Penguin Random House Book Listing)". Penguin Random House . Retrieved March 2, 2020.

- ^ a b Jeffrey Toobin. "Girls Behaving Badly."New Yorker. May 30, 2005.

- ^ "Guide to the Guerrilla Girls Archive 1985-2010 MSS.274". dlib.nyu.edu . Retrieved March 2, 2020.

- ^ a b Adams, Guy (Apr 8, 2009). "Guerrilla girl power: Have America'due south feminist artists sold out?". The Independent. Independent Print Limited. Retrieved June seven, 2016.

- ^ "School of the Art Found of Chicago Commencement Accost" (PDF). Guerrillagirls.com. May 22, 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on October v, 2013. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- ^ Bitches, Bimbos, and Ballbreakers: The Guerrilla Girls' Illustrated Guide to Female person Stereotypes' . London: Penguin. 2003. p. 46. ISBN978-0-14-200101-1.

- ^ Jason, H.W. (1952). Apes and Ape Lore in the Renaissance and Eye Ages. London: The Warburg Institute, University of London. p. 291.

- ^ "Guerrilla Girls". The Art Institute of Chicago.

- ^ "Heart for the Study of Political Graphics". collection-politicalgraphics.org . Retrieved September 29, 2020.

- ^ "Drove of the Middle for the Written report of Political Graphics". www.oac.cdlib.org . Retrieved September 29, 2020.

- ^ "Guide to the Guerilla Girls Annal, 1985-2010 | MSS.274 | Fales Library and Special Collections | NYU". Fales Library and Special Collections | New York University . Retrieved March ii, 2020.

- ^ "Guerrilla Girls". Collections. Tate. Retrieved September 25, 2011.

- ^ "11 Posters Celebrating 30 Years of the Guerrilla Girls – Magazine – Walker Art Center". world wide web.walkerart.org . Retrieved Apr 12, 2016.

- ^ Ryzik, Melena (August 5, 2015). "The Guerrilla Girls, Later 3 Decades, Yet Rattling Art World Cages". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 23, 2016.

- ^ "EXHIBITIONS". Guerrilla Girls . Retrieved June 22, 2019.

Bibliography [edit]

- Boucher, Melanie. Guerrilla Girls: Disturbing the Peace. Montreal: Galerie de l'UQAM, 2010. ISBN ii-920325-32-9

- Brand, Peg. "Feminist Art Epistemologies: Understanding Feminist Art." Hypatia. 3 (2007): 166–89.

- Guerilla Girls. Guerilla Girls: the art of behaving desperately. San Francisco, California: Chronicle Books, 2020. ISBN 9781452175812

- Guerrilla Girls. Confessions of the Guerrilla Girls, with an Essay past Whitney Chadwick. New York City: HarperCollins, 1995. ISBN 0-04-440947-8

- Guerrilla Girls. Bitches, Bimbos, and Ballbreakers: The Guerrilla Girls' Illustrated Guide to Female Stereotypes. London: Penguin, 2003. ISBN 978-0-14-200101-1

- Guerrilla Girls. The Guerrilla Girls' Bedside Companion to the History of Western Art. London: Penguin, 1998. ISBN 978-0-14-025997-i

- Janson, HW. Apes and Ape-Lore in the Centre Ages and the Renaissance. London: Warburg Institute, University of London, 1952.

- Page-Lieberman, Neysa (ed.). Not Ready to Make Dainty: Guerrilla Girls in the Fine art World and Beyond, with essays by Joanna Gardner-Huggett, Neysa Page-Lieberman, Kymberly Pinder, and a foreword by Jane M. Saks, Columbia College Chicago, 2011, 2013, 2017. ISBN 0929911431

- Raidiza, Kristen. "An Interview with the Guerrilla Girls, Dyke Activeness Machine DAM!, and the Toxic Titties." NWSA Journal. i (2007): 39–48. <https://www.jstor.org/stable/431723>. Accessed February 27, 2013.

- Schechter, Joel. Satiric Impersonations: From Aristophanes to the Guerrilla Girls. Carbondale: Southern Illinois Academy Printing, 1994. ISBN 978-0-8093-1868-i

External links [edit]

- An interview with Guerrilla Girls using the names Frida Kahlo and Kathe Kollwitz conducted 2008 Jan. nineteen and Mar. nine, by Judith Olch Richards, for the Archives of American Art

- Complete Chronology of Guerrilla Projects since 1985

- Guerilla Girls records, Getty Inquiry Establish, Los Angeles. Accretion No. 2008.Thou.xiv

- Guerrilla Girls, Brooklyn Museum's Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Fine art

- Guerrilla Girls: 'Yous have to question what you come across' Archived October 19, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, video interview by Tate

- Official website

- The Feminist Future: Guerrilla Girls a video from a talk presented at the Museum of Modernistic Fine art

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guerrilla_Girls

0 Response to "Name the Collective Organization That Protests the Unequal Treatment of Women in the Arts Quizlet"

Post a Comment